Chemistry doctoral candidate and Clean Energy Institute Education & Training Fellow Erin Jedlicka works with Maliya, a 5th-grader at Hilltop Elementary in Lynnwood, WA. (Dennis Wise / UW Photo)

By Owen Freed

August 19, 2019

When Erin Jedlicka was a United States Navy Surface Warfare Officer on the USS Shoup, she was responsible for maintaining and operating the ship’s advanced systems. She quickly learned that an understanding of fundamental science was key to the job, as it governs daily life aboard.

“Chemistry is used to put out fires that could sink your ship and to disinfect spaces to prevent the entire crew from getting sick,” explains Jedlicka, who graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 2012 and completed a three-year commission based in Everett, WA in 2015. “It purifies the water we drink, and is one way used to create oxygen on submarines so the crew can breathe. Navy sailors spend countless hours cleaning off rust and repainting ships to mitigate the reaction between steel and seawater.”

From the Navy to graduate school

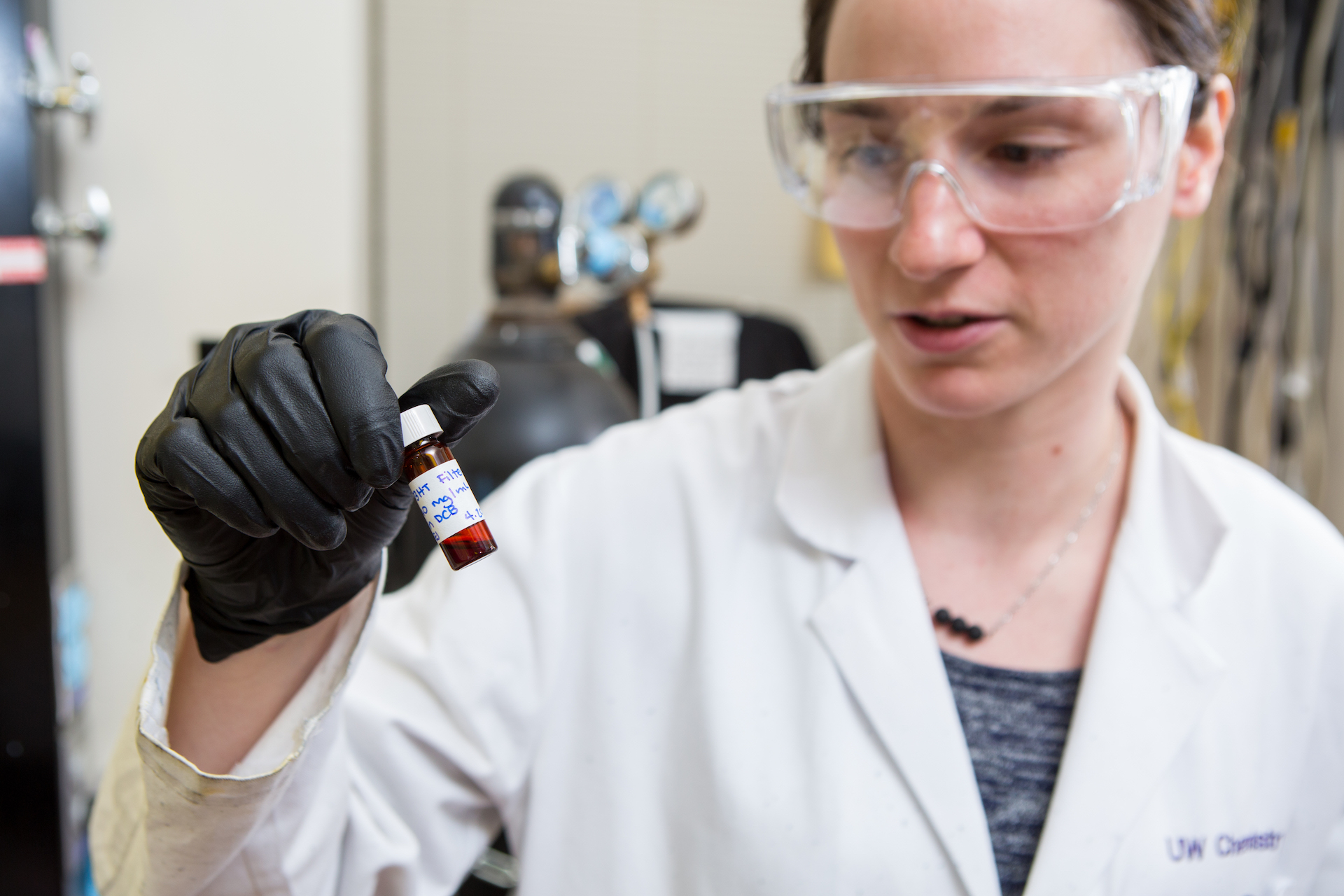

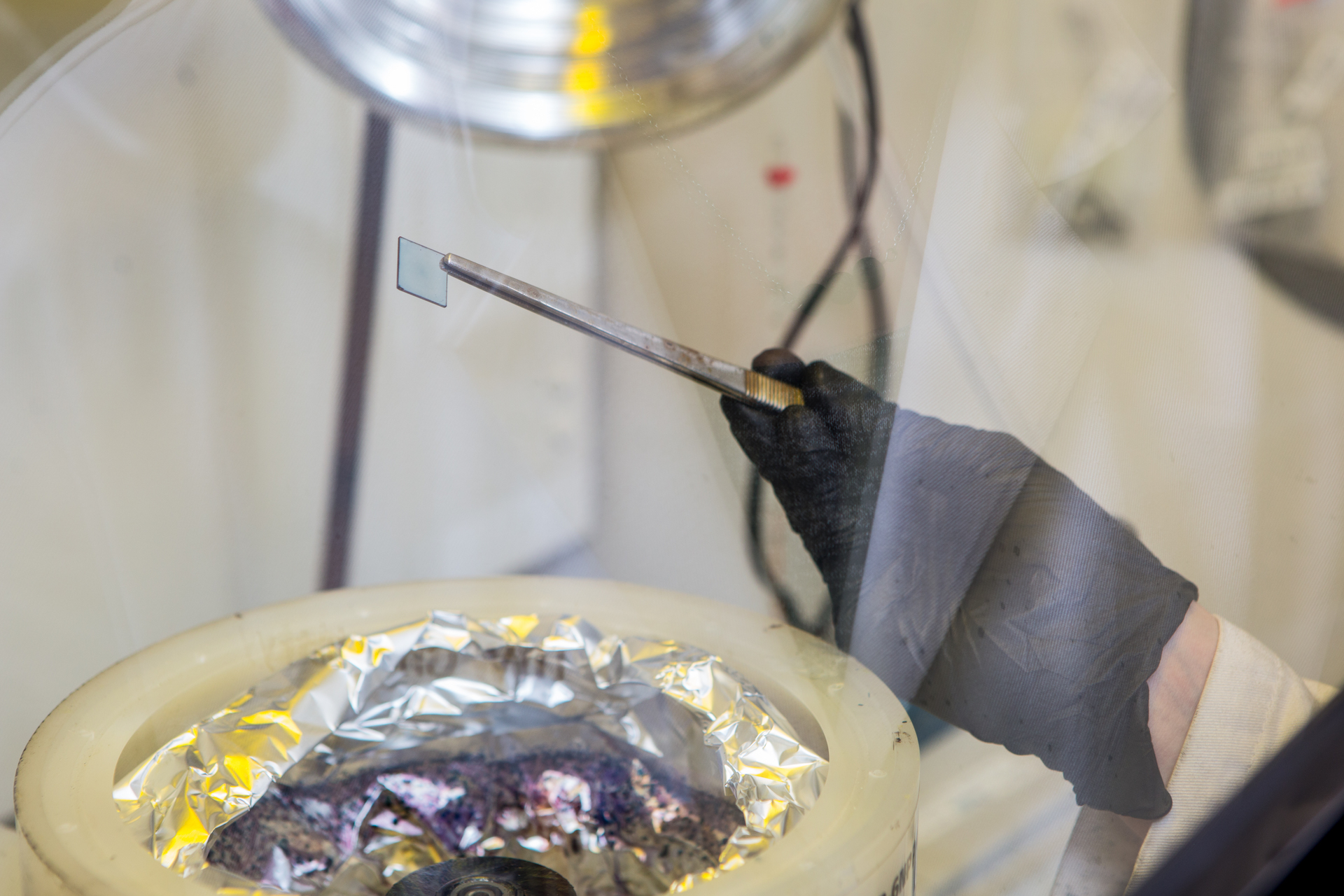

After completing her Naval service, Jedlicka enrolled at the UW and joined Professor David Ginger’s lab group to pursue a chemistry Ph.D. Now in her fourth year, she is researching materials for next-generation solar panels, including perovskites and quantum dots — specially-engineered crystals that can be used to make solar panels more efficient and less expensive.

Jedlicka works with new materials for clean energy in David Ginger’s lab. (Matt Hagen / Clean Energy Institute)

“I decided to pursue my doctoral degree because I saw how important it was to change the perception of chemistry from ‘an unreasonably hard college course that will never apply to real situations,’” says Jedlicka. “Despite the vital chemistry going on all around us, there was fear and misunderstanding of chemistry and ‘chemicals’ throughout my Navy crew. That sense of fear and misunderstanding doesn’t just apply to the Navy — it has huge costs around the world.”

Making science accessible

In her second year as a graduate student, Jedlicka participated in her first K-12 outreach event with the UW’s Clean Energy Institute (CEI) and was inspired by the enthusiasm she saw from young students. She then applied for the CEI Education & Training Fellowship, and has led visits to more than 50 schools, libraries, and science fairs around Washington state this year. A recent visit to Lynnwood’s Hilltop Elementary School was particularly special — her boyfriend’s daughter, Haley, is a 5th grade student there.

As the Clean Energy Institute’s Education Fellow, Jedlicka talks to young students about renewable energy and power grids. (Dennis Wise / UW Photo)

As the Clean Energy Institute’s Education Fellow, Jedlicka talks to young students about renewable energy and power grids. (Dennis Wise / UW Photo)

“What do you think I do?” Jedlicka asks the students.

Haley exclaims, “She works with lasers!” “Oohs” and “ahhs” ring out. Jedlicka then asks them to guess the land area that could generate enough power for the entire United States if covered in solar panels. It’s actually less than one percent, just a small corner of Arizona or Nevada.

“Why haven’t we done that already?” asks one student.

“Well, just think of a cell phone,” Jedlicka replies. “It’s as thick as it is because of the battery, and it doesn’t even last very long. What if we needed a battery for a whole city, or the whole country? I’m working on better solar panels, and engineers are making better batteries and a smarter power grid so we can get that power where it needs to go.”

Her simplified explanation of the photons and electrons in solar panels seems to fly over some heads, but the real-world effect becomes clear as the students get to work on their “solar spinners.” The students carefully tape the wires of small motors to the edges of wafer-thin silicon solar cells, then enclose the contraptions inside petri dishes and line up to place their spinners under a high-intensity lamp. Sure enough, the motors start to turn. But for those whose spinners won’t spin, Jedlicka comes to the rescue, carefully re-taping wires and helping replace cracked panels. As one student’s spinner finally whirrs to life after several adjustments, she says with a smile, “This is what a career in science is!”

Students at Hilltop Elementary (Lynnwood, WA) attach small motors to solar panels. The devices spin when exposed to sunlight or a high-intensity lamp. (Dennis Wise / UW Photo)

Students at Hilltop Elementary (Lynnwood, WA) attach small motors to solar panels. The devices spin when exposed to sunlight or a high-intensity lamp. (Dennis Wise / UW Photo)

A group of intrepid students asks to test their spinners out on the blacktop of the school’s playground. Maliya notes that hers is spinning even faster under the grey spring sky than it did under the lamp. “It goes to show you how a solar panel can still power your house when it’s cloudy!” Jedlicka explains.

Michael proclaims, “I want my parents to put solar panels on the roof of our house!”

Kamryn declares her excitement for middle school, just a summer away. “STEM class is my favorite,” she says, “and I especially love chemistry. And explosions!”

Moments like these are Jedlicka’s favorite part of volunteering with K-12 students. “I really believe the impact of our outreach is more than just a fun science lesson,” she says. “When you ask a kid what they want to be when they grow up, they’ll pick a career they know about, like sports or being a movie star. I want to show students what it’s like to be a scientist and help make them comfortable with science, rather than scared of it. Their future is one in which clean energy is the main source of electricity, and any of them could be one of the scientists and engineers making it possible.”

A future Husky assembles a solar spinner. (Dennis Wise / UW Photo)

A future Husky assembles a solar spinner. (Dennis Wise / UW Photo)

After she completes her Ph.D., Jedlicka sees her own future in education. She hopes to combine her love of chemistry, teaching, and service as a professor at a small university or community college — where she can continue to inspire the clean energy leaders of tomorrow.

K-12 teachers can request a classroom visit from CEI’s Education Fellow and volunteer Clean Energy Ambassadors here.